One World, Three Visions: How Early Maps Changed the Way We See the Earth

- Agora Old Prints and Maps

- Jan 5

- 4 min read

What Do Maps Really Show?

Maps are often perceived as objective representations of the world. Lines, grids, coastlines, and place names appear to offer certainty and precision. Yet antique maps tell a different story. They reveal not only where places were believed to be, but how the world itself was imagined, understood, and ultimately controlled.

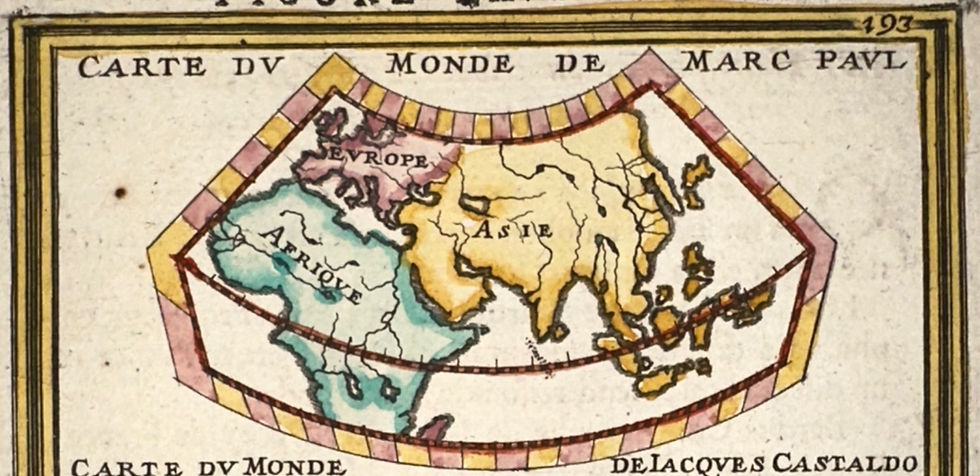

This remarkable engraving from Alain Manesson Mallet’s Description de l’Univers (Paris, 1683) captures that idea perfectly. Within a single plate, Mallet presents three different world maps attributed to Marco Polo, Jacques de Gastaldi, and Miguel Lopez. Together, they form a visual narrative of humanity’s evolving relationship with the Earth—from storytelling and imagination, to measurement and science, and finally to power and administration.

Alain Manesson Mallet and the Seventeenth-Century Mind

Alain Manesson Mallet (1630–1706) was a French military engineer, mathematician, and cosmographer. His career combined practical military knowledge with a deep interest in astronomy, geography, and global systems. Description de l’Univers was conceived as an encyclopedic work—designed not merely to describe the world, but to explain how it functioned, how it was observed, and how it could be represented.

Unlike many mapmakers who sought to present a single authoritative image of the Earth, Mallet chose a comparative approach. By placing different worldviews side by side, he encouraged readers to understand cartography as a product of its time—shaped by available knowledge, cultural assumptions, and political realities.

The World as a Story – Marco Polo

The upper map, titled Carte du Monde de Marc Paul, represents a world shaped by narrative rather than measurement. Attributed to Marco Polo, it reflects the geographical imagination of late medieval Europe.

In this vision, Asia dominates the world, vast and alluring, reflecting the influence of Polo’s travel accounts and the enduring fascination with the riches of the East. The Americas are entirely absent, as this worldview predates the Age of Discovery. Europe and Africa appear smaller, secondary to the great landmass of Asia.

This is not a navigational tool. There are no precise coordinates, no consistent scale. Instead, the map functions as a visual extension of storytelling—a way to organize hearsay, observation, and wonder into a coherent image of the world. Geography here is descriptive, not analytical.

The World as a Measurable Object – Jacques de Gastaldi

The central map, attributed to Jacques de Gastaldi (c.1500–1566), marks a profound shift. Gastaldi was one of the most influential cartographers of the Renaissance, working in Venice at the heart of European trade and exploration.

Here, the Americas clearly appear, reflecting the transformative impact of the great voyages of discovery. Latitude and longitude lines impose order upon the globe, allowing distances to be calculated and coastlines to be compared. The Earth becomes something that can be measured, studied, and navigated.

This map bridges classical knowledge and modern science. Rooted in Ptolemaic tradition yet informed by new empirical data, it represents a world transitioning from imagination to observation. Cartography becomes a scientific discipline, essential to navigation, commerce, and exploration.

The World as an Object of Control – Miguel Lopez

The lower map, attributed to Miguel Lopez, reflects the cosmographic tradition of the Spanish Empire. Likely inspired by figures such as Juan López de Velasco, official cosmographer to the Spanish Crown, this representation belongs to a world already divided, classified, and administered.

A strict grid system dominates the map. Continental proportions are more balanced, and the layout reflects a distinctly European-centered worldview. The Americas are no longer mysterious lands but organized territories—mapped for governance, taxation, and imperial control.

At this stage, maps are no longer neutral. They are instruments of authority, serving political and administrative purposes. Geography becomes inseparable from power.

One Plate, Three Worldviews

By presenting these three maps together, Mallet offers more than a lesson in cartography. He reveals a progression:

The world first told through stories

Then measured through science

Finally controlled through power

This single engraving encapsulat

s centuries of intellectual transformation. It reminds us that maps do not simply reflect reality—they shape it.

Why These Maps Still Matter

Even in the age of satellite imagery and digital navigation, maps continue to influence how we understand the world. They frame perspectives, prioritize certain places, and reflect underlying values.

Antique maps like this one endure because they show us not only where people believed the world to be, but how they believed it should be understood. They are historical documents of knowledge, ambition, and imagination.

This engraving from Description de l’Univers stands as a powerful reminder: the history of maps is also the history of how humanity learned to see the Earth.

Comments